Why Your Attempt to Change the World Will Fail (Unless You Have a Solid Theory of Change)

There are often many unseen steps between your actions and the change you want to see in the world. That’s why a robust Theory of Change matters: it makes those hidden steps visible, showing how what you do today connects to the outcomes you ultimately want to achieve.

Many of us that want to “do something good” begin with scattered actions: a promising idea that fizzles out, or a course we forgot to apply to.

We see this time and time again: the biggest barrier isn’t lack of passion or talent, it’s not knowing how the actions you can take translate into the change you hope to see.

That’s why it’s crucial to have a plan when you set out: a Theory of Change. Think of it like a GPS for your impact, telling you where you’re going, showing the route and the traffic conditions, and helping you with what to do if a road is blocked.

In our Moral Ambition Circle program, we invite participants to zoom out and map the path between what they do and the difference they want to make. In turn, their Theory of Change becomes a simple, adaptable, and grounding tool that helps turn ambition into impact.

What is a Theory of Change?

A Theory of Change shows how your actions lead to the impact you want to see. Jamie Spurgeon, Monitoring & Evaluation expert at The Mission Motor, describes it as a causal chain.

“It is a map that takes you from the activities that you’re carrying out to the impact you want to create,” he explains.

In other words, it’s not just what you’ll do; it’s why those actions matter, how they are expected to lead to change, and what assumptions must hold for things to work.

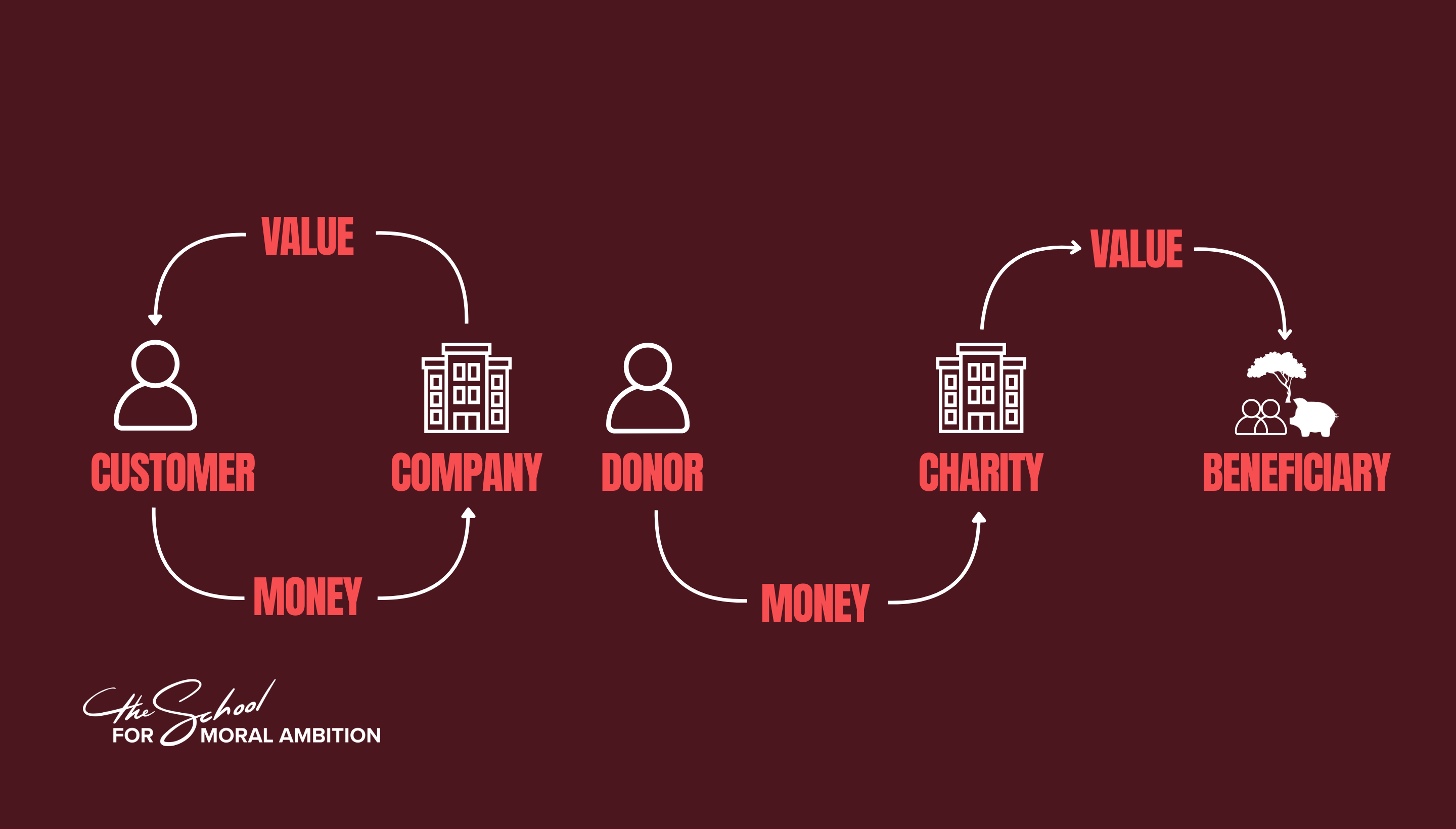

Nonprofits build Theories of Change because they lack the natural feedback loops that businesses rely on. A business quickly knows when something isn’t working: revenue drops, customers leave. A charity, on the other hand, can operate for years without clear evidence that it is making progress. A Theory of Change forces organizations to articulate how they expect change to happen, and what success should look like.

Imagine a nonprofit focused on improving literacy among children in rural schools. They start a reading program, distributing books and training teachers, but months go by, and they don’t see obvious changes. Unlike a business, where slow sales would immediately signal a problem, the nonprofit can’t instantly tell if children’s reading skills are improving.

By creating a Theory of Change, the organization maps the steps between their activities (teacher training, book distribution) and their ultimate goal (higher literacy rates). This helps identify measurable milestones and adjust their approach based on early data.

A Theory of Change isn’t just for organizations: individuals benefit just as much. A personal Theory of Change turns broad concern into a focused contribution, clarifying what change you want to work toward and how you can realistically contribute. It’s useful not only for career changes or new projects, but also for guiding volunteering, intrapreneurship, movement building, and more intentional choices about where you invest your time and energy.

How a Theory of Change Works

A strong Theory of Change brings together several elements that create a coherent picture of how change might unfold: you start with inputs or activities, which produce outputs, leading to intermediate outcomes, ultimately culminating in your final goal.

Although formats may vary, we’ve broken down the main components of a Theory of Change into six key elements:

1. Define your ultimate impact

This is the long-term effect or change you hope to see; the ultimate goal of your work. Clarity here is crucial. This should be a concrete description of what meaningful progress would look like and who stands to benefit from it.

For example, instead of simply saying “improve education,” you might specify “increase literacy rates among children aged 6-10 in rural districts”.

2. Identify long-term outcomes

Long-term outcomes are the necessary shifts that must happen to achieve your vision. These could involve changes in behaviours, systems, or policies. An example that would fit the educational goal mentioned above could be: “Local schools implement weekly reading programs consistently.”

"If you discover that your program doesn't work, that's a cause for celebration."

3. Map key milestones

Milestones signal progress along the way. These are specific achievements or intermediate outcomes that indicate you’re moving toward your ultimate impact. Tracking milestones helps you answer the questions: “Is this approach working?”

As Nicoll Peracha, Director and founder of The Mission Motor, writes:

"If you discover that your program doesn’t work, that’s a cause for celebration. Because what's the alternative? Continuing the program would be a waste of time and resources."

4. Determine stakeholders

Every Theory of Change relies on stakeholders. These are the people, groups, or institutions whose actions influence the change you want to see. Understanding who they are and how they affect your outcomes is essential for designing effective activities.

Following the education example, these stakeholders could include parents, teachers, or local government officials.

5. Decide activities

Once you’ve mapped your stakeholders and desired outcomes, identify the actions you will take to drive change. The key is focus: doing a few things well is better than trying to do everything at once. For example, these can include conducting training sessions for teachers, creating educational materials, or partnering with NGOs.

6. Record assumptions & evidence

Every Theory of Change rests on assumptions about how and why change happens. Explicitly stating your assumptions and backing them with evidence makes your Theory of Change actionable and testable. Reflect on the questions you need to answer, the uncertainties you face, and the evidence you’ll gather to know whether you’re making progress.

A Theory of Change is therefore both a strategic tool and a reflective one. It moves you from asking “What do I want to do?” to ask “What needs to change, and how can I contribute to it?”

Common Mistakes for Do-Gooders (and How to Avoid Them)

Even the best-intentioned projects can stumble if their Theory of Change is not set up well. Jamie shares some common pitfalls he regularly sees in organizations and individuals, and explains how to avoid them.

Cloudy Visions

One common pitfall is vagueness. Describing your goal as “making the world better” feels good, but it makes it almost impossible to plan meaningful action. Impact requires specificity: clarity about the problem, the people involved, and the change you want to see.

Jamie adds: “First, sit down and define both the problem you’re trying to fix and the stakeholder group. The Theory of Change should clearly articulate what change you’re trying to see within those stakeholders.”

When the target remains vague — “people,” “communities,” or “society” — activities easily miss the mark. Without clarity on who holds power or influence, it becomes unclear whose behavior you are trying to shift, and therefore what progress even looks like.

Leapfrogging

A common issue is making overly large jumps between steps. This often shows up as assuming a single activity will directly lead to a major impact, without accounting for the intermediate changes required along the way.

“Breaking things down into realistic steps makes the process more credible and useful,” Jamie explains.

A good rule of thumb is to ask: what needs to change first? Identify the initial shift in behavior, incentives, or systems, and then map each causal step explicitly.

Putting the Cart in Front of the Horse

Another common mistake is starting with the activities you’re already doing. Designing a Theory of Change by listing actions first can quickly become chaotic and unfocused.

“Start with your impact and work backwards,” Jamie explains. “When you map it forward, it becomes messy very quickly, and you often end up with activities that don’t meaningfully contribute to change.”

A stronger approach begins with the outcome you want to achieve, then works backward to identify what needs to change, in what sequence, and who needs to be involved. Only then does it make sense to decide which actions you personally should take.

"Many people create a Theory of Change just because that's what they've seen other people do."

Shiny Object Syndrome

It’s tempting to try to do everything at once, creating sprawling documents that attempt to cover every possible angle. But a strong Theory of Change is focused, not exhaustive.

Collecting data early helps measure progress pillar by pillar. “Even if you start broadly,” Jamie explains, “looking at the data you’re getting can help you narrow your priorities or realize that some parts of your Theory of Change don’t need attention yet.”

Feedback plays a similar role. Testing your ideas with the people and groups involved helps clarify what you’re trying to achieve and why.

Set-it and Forget-it

One of the biggest misconceptions is viewing the Theory of Change as a static document.

“Many people create a Theory of Change just because that’s what they’ve seen other people do,” Jamie says. “But if you create it and then don't build architecture to revisit it, then it doesn’t work.”

A Theory of Change is most valuable when visited regularly as a tool for reflection and adaptation. Jamie recommends setting up a plan from the start — perhaps quarterly check-ins — to review assumptions, evidence, and progress.

In the Circle program, this mindset of constant learning is a defining aspect of moving from aspiration to action.

Your Impact Compass

Developing a personal Theory of Change is both an analytical exercise and an emotional one. It forced you to make choices: to let go of the illusion that you can solve everything, and instead commit to the part of the world where you can genuinely move the needle.

When the work becomes messy or slow, as it inevitably will, your Theory of Change becomes your compass. It reminds you why you’re doing this, what progress looks like, and where your energy is best spent.

A Theory of Change won’t tell the full story of your impact. But does something more valuable: it helps you start the story deliberately.

If you’re ready to build a Theory of Change to increase your impact, learn more about our Moral Ambition Circle program and get started now.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

.jpg)